Mumbo-jumbo or a science ?

Whatever the arguments advanced by scientists and sceptics against water divining, the Brisbane Amateur Turf Club's decision to bore for water on a spot picked by a diviner at Doomben racecourse has an impressive precedent. in 1938 Mr. E. Bestman, a diviner attached to the Queensland Government's Irrigation Department, divined the spot for the 25 gallons-a-minute bore now in use at Doomben. Mr. Bestman, who retired in that year after four years as a 'water finder,' had no successor, as the post was abolished.

Finding of water is but one of the branches of divining or dowsing, origin of which is lost in antiquity. It is usually practised by the diviner holding a forked twig, which by twisting in his hands is supposed to lead him to the spot below which is underground water or a metallic lode.

Many professional water diviners are themselves sceptical of the claims of another class of diviner. This is represented by those who claim to be able to solve murder mysteries and the like and divine almost everything except the winning number in a lottery.

The forked twig of hazel or willow was used by prospectors for minerals in the Harz Mt. mining district of Germany in the 15th century. It was brought to Britain in Elizabethan days by merchants for Cornish miners. Use of the rod was transferred to water finding when mining declined in Cornwall.

University of Queensland geologists, in common with scientists all over the world, emphatically state that there is no scientific principle involved in dowsing.

Opinions on dowsing range from the Encyclopaedia Britannica's statement that "a wide spread faith exists, based on frequent success, in the dowsers power" to a New Zealand scientist's denunciation of it. last year as "just numbo-jumbo". A British scientist, the late Professor Sir William Barrett, founder of the Society for Psychical Research many years ago fully investigated dowsing. Among his publications was "A Monograph on the So-Called Divining Rod.' Professor Barrett was satisfied that the rod twisted without any intention or voluntary deception by the dowser and ascribed the phenomenon to 'motor automatism' on the part of the dowser. This was a reflex action excited by some stimulus upon his mind. The stimulus could be either a sub-conscious suggestion or an actual impression, obscure in nature, from an external object. The dowser's power lay beneath the conscious, like the homing instinct in certain birds and animals.

Colonel A. H. Bell, as president of the British Society of Dowsers, recently suggested dowsing should be given the modern name of Radiesthesia or Radio Perception. Causes of the reflexes affecting the divining rod, according to Colonel Bell, are mainly electromagnetic radiations, lonisation, change of electric potential, and change in magnetic field acting on the delicate nervous system of the human body. In the same way, diagnosis of illness by the divining pendulum was explained by the illness causing a change in the nature of radiations from the body.

He differed with Professor Barrett in that he believed the cause of the muscular reflexes was directly objective and physical, and that they were not due to 'some tortuous process of the subconscious mind.'

The New Zealand scientist was 30-year-old Patrick Ongley. At a British Association meeting in London in September last year he described experiments with 75 diviners. Ongley started a row when he said that in one test a diviner had diagnosed varicose veins in a wooden leg. It was just mumbo-jumbo, he said. Several diviners with twigs tried to trace the course of an underground stream, and each had given a different answer. They had failed to discover buried bottles of water, and when asked the depth of an 18 inch spring had said '50 feet.' The scientist claimed that the slightest movement of the wrist could make a hazel twig twitch violently.

Methods used by diviners vary considerably from the traditional hazel forked twig. Some dowsers prefer a beech or willow twig, others a piece of wire, a watchspring, or a pendulum.

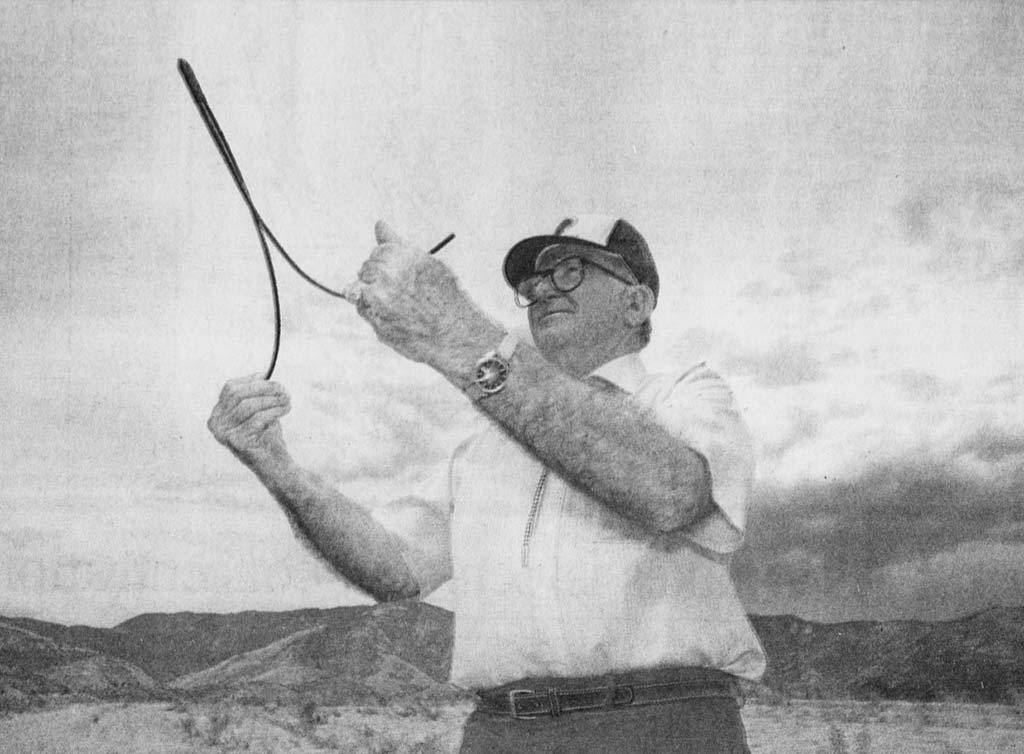

Last week I watched a diviner, using a length of copper wire, at work.

To the sceptic, the method employed would seem to allow no chance of movement of the hands sufficient to cause the heavy wire to loop, corkscrew fashion, while rigidly held in a bow above the diviner's head. It's something inside me, some people think it is electricity, others magnetism, he said, when asked to explain his powers. Farmers I spoke to would not say whether they believed in water divining or whether they thought it was trickery. But most said they would not risk at least £200 to sink a well or a bore unless they had a diviner pick the spot. Diviners' fees range up to £20 for selection of a site on a money-back-if-no-water basis', small consolation if a farmer has already spent £300 sinking the bore or well.

However, in many cases, if the farmer still wants water, he will, undeterred, change his diviner next time.

Some diviners do not need any "implements". Last June a Capetown mining company hired 19 year-old Pieter van Jaarsveld to hunt minerals under a six months contract. Van Jaarsveld says that he can locate water, gold, and other minerals by distinctive light rays coming from the earth. He sees a black ridge before his eyes when passing over a gold reef, diamonds give off a heat haze, and water beams of moon light.

In 1947 when on his way to Tanganyika on a dowsing expedition for a Johannesburg mining syndicate, he stopped at a hotel In Salisbury (Southern Rhodesia). The town was in the midst of a water shortage. Van Jaarsveld called the ma ager, who called the mayor, and the youth was driven around the town until he saw some moon beams. The sceptical city council put its engineers to work. After 18 days drilling, a 403,200 gallons a week supply was struck under 140 feet of rock.

Use of a divining pendulum for testing food or drink for contamination or diagnosing an illness is a branch of divining far removed from straight water divining and open to great scepticism.

In Exmouth (Devon) an 82 year-old retired businessman, John Taverner, tests his food with a pendulum before eating or drinking. Taverner, who has been divining for 10 years, began testing his food after being poisoned by eating Irish stew. He claims that if the pendulum swings around smoothly in an anti-clockwise circle the food is safe to eat. But an erratic anti-clockwise swing puts him off the food completely.

A London firm which manufactures divining rods sells about 200 pendulums a year, and many of these are used for testing food. Whatever the opinions of scientists and the conclusions of further investigations into the realm of dowsing, it will take a great deal to shake the faith of many men on the land. A lot of them are amateur diviners themselves and will dig their well where the forked twig twitches in their hands.

By Clem Lack, Jnr.

The Courier Mail, 2 September 1949